9 November 2023

Dear Sir,

US President Joseph Robinette Biden

Next week, President of the Republic of Indonesia Joko Widodo will visit the United States to attend the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit 2023. Along with this agenda, we have been informed that there will be bilateral meetings between the Governments of Indonesia and the United States to discuss various strategic issues, including regional security and clean energy transition. In addition, there will be many further discussions regarding the collaboration for the use of critical minerals for electric car batteries.[1]

In this regard, we, Indonesian civil society organizations, would like to express some of our concerns about the current situation of nickel mining in Indonesia. In number of studies that we conducted, we identified number of problems, including; 1) The weakness of nickel mining governance in Indonesia; 2) Massive ecological damage arising from mining governance imbalances; and 3) Human rights violations resulting from fragile mining governance.

Concerns with an Indonesian-US CMA

Issues of fragility in nickel mining governance

The fragility of mining governance in Indonesia can be seen in the following regulations:

- Law Number 3 of 2020 concerning Minerals and Coal. One of the problematic provisions in the law, which was revised in 2020, is removing the authority of local governments in mining governance. This cuts off the participation of local communities to submit objections and complaints to the local government, because its authority has been recentralized to the central government. Communities are not given the freedom to reject mining, instead mining-rejecting communities are threatened with criminalization in Article 162 of the law. The provisions of Article 99 paragraph (3) of this regulation also provide leeway for reclamation obligations and post-mining activities for mining entrepreneurs. This has the potential to cause more deadly toxic mine pits. Auriga Nusantara notes that with this policy, the area of ex-mining pits that are threatened with not being reclaimed reaches 87,307 hectares (Auriga Nusantara, 2020). Based on a report from the East Kalimantan Mining Advocacy Network (Jatam), from 2011 to 2021 there were 40 people who drowned in mining pits in East Kalimantan that were not reclamation (Mongabay, 2021).

Law Number 6 of 2023 on Job Creation. This regulation cuts many environmental protections. Among others, it removes the 30% forest area requirement in each province that was previously maintained through the Forestry Law; cuts the involvement of civil society in the preparation of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA); in addition to not involving the community in the process of preparing environmental impacts, they also no longer have space to file objections. The Job Creation Law has also issued many problematic derivative regulations, for example Government Regulation No. 22 of 2021 allows miners to dump waste into the deep sea using the Deep Sea Tailing Placement (DSTP) method.

• Our analytical study shows that Indonesia’s mining regulations are still very far from the standards of the world’s responsible mining initiative, namely: Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA).

The issue of ecological damage

• Massive nickel mining activities in Indonesia have led to increased deforestation rates. Open-pit mining to extract laterite nickel reserves in fragile ecosystems risks losing biodiversity and high carbon stock forests.

- Monitoring of 330 nickel mining concessions using radar and satellite (GLAD+RADD) from 2000 to the present has recorded deforestation due to nickel mining of 156,281 hectares. This is the deforestation recorded due to legal nickel mining. Three of the 330 concessions we observed: Vale Indonesia in the Soroako Block, Bintang Delapan Mineral, and Aneka Tambang in North Konawe have caused the loss of more than 50% of the High Carbon Forest. Vale and Bintang Delapan Mineral cleared 51,229 hectares of forest categorized as Key Biodiversity Area by IUCN.

- Deforestation by mining companies supplying IWIP in North Maluku during the 2021- 2023 period has also caused the loss of 5,780 hectares of natural forest and caused damage to the watershed structure in the upstream areas.

• The construction of coal-fired power plants to process Indonesian nickel has resulted in a much higher COS footprint than nickel produced in other countries. Indonesia’s coal capacity at 40.6 GW by 2022. The Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park in Sulawesi (IMIP) for example “will soon have almost as much coal-fired power generation capacity (at least 5 GW) as Mexico, or Pakistan“.

• The HPAL process produces large amounts of tailings and causes pollution of surrounding waterways and runoff into ocean areas that are important for the livelihoods of indigenous and local communities. One example is the pollution and even destruction of the Sagea watershed, due to the destruction of the forest ecosystem in the upper Sagea River.[2] The results of sea water testing in Weda Bay, Central Halmahera, and Buli Bay, East Halmahera, both in North Maluku Province, in early September, showed this indication. The content of hexavalent chromium (Cr), nickel (Ni) and copper (Cu) exceeded the quality standard threshold set in Government Regulation Number 22 of 2021 concerning the Implementation of Environmental Protection and Management.[3]

• Captive power plant operations and heavy vehicle activities in nickel industry areas, such as Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP) and Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP), are thought to have contributed greatly to the high dust concentrations (PM10 and PM2.5 ) in the affected villages. The poor air quality has led to high cases of Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI) in Lelilef Village, Central Halmahera Regency, and in Bahodopi Sub-district, Morowali Regency, as recorded by the local Community Health Center (Puskesmas).

Human rights violations, no meaningful participation, and manpower issues

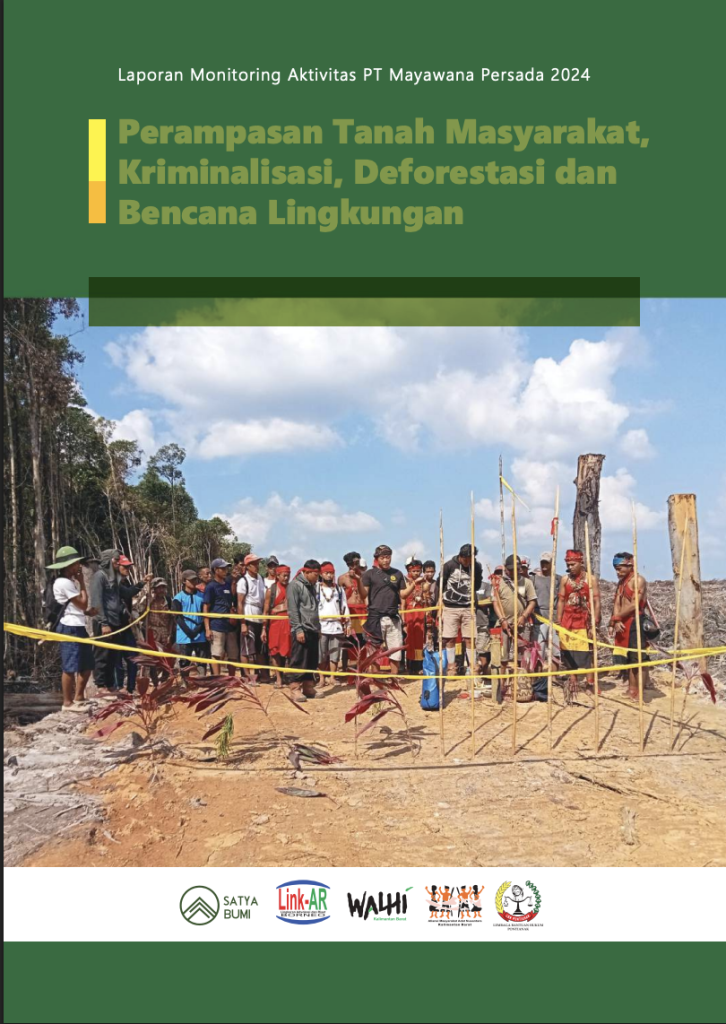

• Conflicts between local communities and nickel mines are increasing the criminalization of local communities and environmental defenders.

• The mining activities of the IWIP supplier company in North Maluku have also driven the Hongana Manyawa ethnic group out of the forest where they live.[4]

• Local villagers in key mining and refining areas expressed concern about the negative impacts they face, particularly in relation to agriculture and access to community infrastructure, such as access to clean water and the threat of natural disasters.[5]

• Riots have occurred and led to the deaths of workers due to poor safety and wage conditions; reports detail long working hours without breaks, pay cuts, and lack of adequate safety and respiratory equipment.

Trade Fairness Issues and Their Impact on Society

The Government of Indonesia in negotiating various international trade agreements is always exclusive and lacks public participation, including in negotiating issues related to extractive mining. This is even though the extractive issues negotiated have a very broad impact on the lives of small communities.

Indonesia for Global Justice (IGJ) noted that 8 out of 10 international trade agreements involving Indonesia did not involve affected communities in the negotiation process. If there is no community involvement in trade negotiations, where is trade justice for affected communities? In fact, exploitation of natural resources occurs and is even commited to in various trade agreements which do not give the public the opportunity to express “rejection” of unfair trade.

Apart from that, the trade pillar in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) negotiations should be a screening of raw materials such as nickel and coal which cause environmental damage and socio-social losses. The United States in trade facilitation (trade facilitation) proposes the existence of environmental and labor standards in the trade aspect. This should be strengthened by rejecting all forms of raw material products produced from mining processes that damage the environment and harm society.

Therefore, we urge the United States to strengthen its commitment to environmental standards in the context of trade facilitation that is being negotiated in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) with Indonesia. In order to prevent nickel trading with Indonesia which results in deforestation and ecological damage as well as social impacts.

Demands

The massive exploitation of natural resources without the development of strong mining governance has serious consequences for ecological damage and human rights violations. The risk of environmental damage and human rights violations in the nickel value chain has been reflected in various nickel mining areas in Indonesia, one of the world’s largest nickel producing countries.

The operation of coal-fired power plants in industrial areas also increases the concentration of greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere and adversely affects global climate change. This is not in line with the Net Zero Emissions (NZE) target by 2060 or sooner. In addition, the emissions released by these power plants have the potential to reduce the health quality of local residents.

Electric vehicle batteries are expected to play an important role in the shift to a carbon-neutral economy. Findings that nickel extraction is fraught with human rights abuses and environmental damage must be addressed and mitigated if a just transition to renewable energy is to be achieved.

Based on the results of civil society coalition monitoring in the field that shows the many environmental risks and human rights impacts of nickel mining activities, it is necessary to reform mining governance policies so that they are responsible and based on human rights. In fact, President Jokowi should place a moratorium on the issuance of critical mineral mining licenses throughout Indonesia.

Therefore, we ask the US Administration under the leadership of President Joe Biden to see and consider these conditions in discussing trade agreements with Indonesia.

Sincerely,

1. Satya Bumi

2. Indonesia for Global Justice (IGJ)

3. Ecological Action and Emancipation of the People (AEER)

4. WALHI National Executive

5. WALHI South Sulawesi

6. WALHI Southeast Sulawesi

7. Forest Watch Indonesia (FWI)

Footnote:

[1] https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/indonesia-president-scheduled-meet-us-president-biden-this-month-2023-11-07/

[2] https://fwi.or.id/tindak-pelaku-pencemaran-sungai-di-das-sagea/

[3] https://www.kompas.id/baca/nusantara/2023/11/06/perairan-halmahera-tercemar-logam-berat

[4] https://www.instagram.com/reel/CzVpIjVPQrf/?igshid=djh4YWlyZGpzc25n

[5] Powering electric vehicles: Human rights and environmental abuses in Southeast Asia’s nickel supply chains (business-humanrights.org)